The Kurdistan National Congress stressed the need to hold the perpetrators of the Dersim massacre accountable, and said: “A major military attack was launched by an official decision of the Turkish state and government with the aim of eliminating the people of Dersim.”

The Democratic Alevi Associations (DAD), HDP, EMEP, the Amed Branch of the Alevi Bektashi Federation ‘Pir Sultan’, the Socialist Councils Federation (SMF), Federation of Dersim Associations (DEDEF), the Federation of European Dersim Democratic Union (ADEF) organized a tribute to Seyit Rıza in Dersim, Seyit Rıza Square. Seyit Rıza had been hanged at 19.38 of 4 May.

The Democratic Society Congress (DTK) said on the occasion of the anniversary of Dersim Genocide: “The Dersim Massacre is one of the bloodiest stages of the genocide and assimilation policies that started with the establishment of the nation state.

Summary, in English

Environmental destruction has long been used as a military strategy in times of conflict. A long-term example of environmental destruction in a conflict zone can be found in Dersim/Tunceli province, located in Eastern Turkey. In the last century, at least two military operations negatively impacted Dersim’s population and environment: 1937–38 and 1993–94. Both conflict and environmental destruction in the region continued after the 1990s. Particularly after July 2015, when the brief peace process that began in 2013 ended, conflict between the Turkish state and the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) resumed and questions arose about the cause of forest fires in Dersim. In this research we investigate whether there is a relationship between conflict and forest fires in Dersim. This is denied by the Turkish state but asserted by many Dersim residents, civil society groups, and political parties. We use a multi-disciplinary approach, combining methods of qualitative analysis of print media (newspapers), social media (Twitter), and local accounts, together with quantitative methods: remote sensing and spatial analysis. Interdisciplinary analysis combining quantitative datasets with in-depth, qualitative data allows a better understanding of the role of conflict in potentially exacerbating the frequency and severity of forest fires. Although we cannot determine the cause of the fires, the results of our statistical analysis suggest a significant relationship between fires and conflict in Dersim, indicating that the incidence of conflicts is generally correlated with the number of fires.

In contemporary Turkey, discussions on the concept of ethnicity and religiosity continue to maintain their utmost importance in politics and daily social life. In this context, Alevi and Kurdish identities have come to the fore with mass representation marked by protests and violence. In spite of the importance of Kurds and Alevis for the history of Turkey, one specific group, namely the Kurdish Alevis, has escaped the attention of the international world. Although wide interest upon the topic in the international academic sphere, there are very limited academic works about Kurdish Alevis in general. Who are the Kurdish Alevis? What are the particular conditions for its association with the Kurdish identity, Alevi religion, and the history of Turkey? What has been the role of Dersim within Kurdish Alevism? The main purpose of this edited volume, the first of its kind, is to contribute to the understanding of these and other questions. Based on six perspectives from scholars from various disciplinary, this approach will present new insights on contemporary research and discussions on the issue.

–

Submitted to the Institute of Social Sciences

in partial fulfillment of the requirements

for the degree of Master of Arts

After the on-going discussion with opposition Republican People’s Party (CHP) Chairman Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu about the “Dersim incidents”, Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan apologized for what happened during “one of the most painful and most tragic events in recent [Turkish] history”, as he put it.

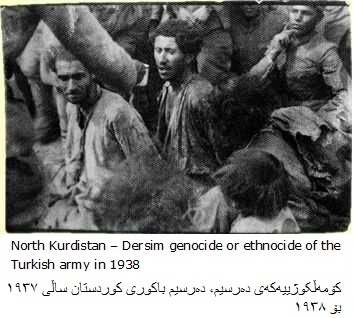

The so-called “Dersim Massacre” refers to the violent suppression in 1937/38 of the local population of Dersim, now called Tunceli Province (eastern Anatolia). Some sources speak of tens of thousands of Alevi Kurds and Zazas that were killed and thousands more that were forced into exile.

Erdoğan’s speech at the Extended Meeting with Provincial Chairs of the Justice and Development Party (AKP) was based on four documents quoted by the PM.

“I apologize”

The second document dated 8 August 1939 was sent by the Gendarmerie General Command to the premiership high prefecture. In included a record of how many people died, survived and were forced to relocate.

Erdoğan quoted, “It is stated in this document that a total of 13,806 people were killed in 1936, 1937, 1938 and 1939. The signature underneath is very interesting. Faik Öztrak. The Minister of the Interior.”

The CHP was the ruling party at the time. Erdoğan addressed Kılıçdaroğlu as the present party chair and asked if he was going to apologize.

“If we have to apologize on behalf of the state and given that such literature exists, I apologize”, Erdoğan announced.

Apology from CHP Provincial Chairman

Subsequent to Erdoğan’s speech, the CHP Provincial Chairman of Diyarbakır (Kurdish-majority province in south-eastern Turkey), Muzaffer Değer, followed the prime minister’s calling and apologized for the incidents that happened in Dersim at the time.

CHP Faction Deputy Chair Hamzaçebi and Deputy Party Chair Tekin on the other hand criticized Erdoğan’s statement.

“We have to face our past”

Değer said in an interview with bianet that people from all over Turkey called him after his statement to express their appreciation and to congratulate him.

“We have to face the past if we made a mistake. If the CHP made a mistake in these incidents, the CHP has to apologize. We cannot face our past without revealing the naked truth”, Değer remarked.

Negative reaction of the CHP

On the other hand, also negative reactions in answer to Erdoğan’s speech were voiced in the ranks of the CHP. CHP Faction Deputy Chair Akif Hamzaçebi criticized that in the prime minister’s eyes all insurgents became victims. He blamed Erdoğan of making “cheap” politics.

In Hamzaçebi’s opinion, Erdoğan created separatism by spilling enmity, hate and anger. He added that the prime minister declared war to the republic.

CHP Deputy Chairman Gürsel Tekin said in a written statement, “I congratulate the prime minister. With his language, style and statement he put dynamite into the foundation of the unity of our country. He managed to pave the way to make everybody enemies and turn against each other. (…) What is left to say? What is the prime minister’s next step? What is the ultimate goal of this campaign?” Tekin questioned. (IC/EKN)

The Dersim region, overwhelmingly populated by Alevi Kurds, resisted the centralization policies of the Ottoman Empire for many decades. While the Alevi Kurds wanted to continue their indigenous cultural and political autonomy, this was considered a threat to the sovereignty of the newly established Turkish Republic (1923). Seyit Riza was one of the most prominent figures in the region, not only as the leader of the Hesenan tribe; he was also seen as a religious figure by the Alevi Kurds in Dersim. In 1937-38, the Turkish military started two major military operations targeting the Dersim region, with the aim of breaking the armed resistance organized by local militias. Gross human rights violations took place in Dersim during these military operations. Although the exact number is still unknown, Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan has said that state documents indicate 13,806 people were killed in the campaign. In January 1937, Seyit Riza sent his son to Aptullah Alpdogan (the commander of a military division in the region governed by emergency law) to find a way to end the armed clashes and mass killings. But Riza’s son was killed, and clashes continued relentlessly. At the end of the year, after Alpdogan promised to spare his life, Riza turned himself in to prevent further killings. We know what happened to Riza through the testimony of Ihsan Sabri, a state official who witnessed his execution (Çaglayangil later became Minister of Foreign Affairs). A quick trial was held, and the verdict read to Riza; he could not understand it, as he was unable to speak Turkish. Riza was sentenced to death and executed immediately.

Military operations did not stop or lose momentum and gross human rights violations continued, including aerial bombardment. Ultimately, the remaining Alevi Kurds were forced to migrate to the western regions of Turkey. Since the archives of the Turkish military are not yet accessible, it is not known what happened to Seyit Riza’s body or where he was buried. Therefore, Seyit Riza’s grandchildren have demanded to be told where his body was taken or buried. Discussions about the Dersim massacre intensified in the mainstream media after a speech by Onur Oymen, a deputy for the Republican People’s Party, in the National Assembly in 2009 in which he called the state policy of killings in Dersim “legitimate.” Since then, Riza’s grandchildren have become more vocal in their demands. But there has been no legal resolution to the questions surrounding his death as yet, and military officials have remained silent.

On May 4, 1937 the government-in-power, Republican People’s Party (CHP), launched the “Punitive Expedition [Operation] to Dersim [Tunceli]” which marked the beginning of Dersim massacres and gave rise to regional operations that later transitioned into extermination operations in 1938.

In his chronicles, the Minister of Foreign Affairs, İhsan Sabri Çağlayangil, has recorded that “[the ‘pundits’] had taken shelter in the caves. The militia used poisonous gas. They poisoned [these pundits] like rats in their caves. They slaughtered Dersim Kurds from all ages. It [the operation] was a bloodshed. So the Dersim issue was done with, the government authority was brought to the village [the east] and to Dersim. Now we can enter Dersim conveniently.”

Tens of thousands of people from all ages were massacred as a result of the several operations that took place between the years 1937 and 1938. Thousands were forced out of and banished from their lands. Likewise, thousands of children, especially girls, were taken from their families and placed into orphanages and given to foster families across Turkey to rid them off their roots as part of a cleansing initiative.

Adopted on 9 December 1948, the United Nations Resolution 260 (III) A, of which Turkey is a signatory nation, states that: “genocide means any of the following acts committed with intent to destroy in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group, as such:

(a) Killing members of the group;

(b) Causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group;

(c) Deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part;

(d) Imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group;

(e) Forcibly transferring children of the group to another group.”

According to the definition set by the aforementioned resolution, the systematically carried out 1937-1938 Dersim massacres against the Kurdish population and the people of Qizilbash (Alevi) religion constitutes an act of genocide. On its 76th anniversary, the victims’ agony persists.

In 2011, Prime Minister Erdoğan stated that, “If there is an apology on behalf of the state and if there is such an opportunity, I can do it and I am apologizing” and left the issue hanging as that point. The Prime Minister has to prove that he was not using the Dersim massacre just as a political tool against the main-opposition.

The pressing demands of the people of Dersim are unequivocal: the city’s name “Dersim” has to be restored to replace “Tunceli”, a name closely identified with the massacre. The government should disclose the burial grounds of the executed rebellious leaders, including that of Seyit Rıza, compensate for the loses of the banished people of Dersim, reveal the truth behind the banished missing children and declassify the military archives. Both the AKP government and the state should fulfill what an apology entails.

It is imperative to confront the truth behind the Dersim Massacre [Dersim Tertelesi in local Kirmanckî] for the construction of societal peace. As Peoples’ Democratic Party, we mourn the thousands that were massacred on the 76th anniversary of the massacre. We call upon the governing party and opposition parties that still carry remnants of similar racist practices today to confront the truth and our history.

TURKEY’S Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP) has demanded an official apology for the 1937 Dersim massacre and the establishment of a truth commission to heal the wounds of one of the bloodiest stains on the country’s history.

HDP MP Alican Onlu tabled a series of parliamentary questions today calling on President Recep Tayyip Erdogan to restore the rights of the people of Dersim, in the largely Kurdish south-east.

He called for a truth & acknowledgement commission to open the archives and court records to the public and for the perpetrators of the massacre to be tried in absentia. Mr Onlu asked for May 4 to be officially recognised as Dersim massacre memorial day.

Measures must be taken to end to the forced assimilation policies that crushed the Kurdish language, beliefs and culture of the people of Dersim, which is known by the official Turkish state name of Tunceli, he said.

A decree signed in the Turkish parliament on May 4 1937 led to an onslaught by the army and the massacre of up to 70,000 people.

The massacre followed a rebellion led by Kurdish Alevi chieftain Seyid Riza against the Turkification policies of Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, the founder of the Turkish republic. Riza was hanged by the state in November 1937 and buried in an unknown location.

Witness statements describe the brutality inflicted on the people of Dersim, including chemical weapons dropped by the Turkish air force. Among the pilots was Ataturk’s adopted daughter Sabiha Gokcen, celebrated as the country’s first female flyer.

Thousands of residents were forced from their land and banished. Thousands of children, especially girls, were taken from their families and placed in orphanages or given to foster families across Turkey as part of an ethnic-cleansing operation.

The people of Dersim named the massacre Tertele, meaning big flood, destruction and extinction.

It is the greatest massacre committed in Turkey after the Armenian genocide. But there have been no lessons learned from the suffering and the incident remains one of Turkey’s darkest days.

Mr Erdogan offered an apology in 2011, but this was seen as an opportunist attempt to embarrass the People’s Republican Party, which was in power at the time.

The HDP demanded that the region be officially renamed Dersim from Tunceli, the name associated with the massacre, and the mass graves be uncovered, especially Riza’s resting place.

The city of Dersim plays an important role in the Kurdish collective memory. Dersim, now the eastern Turkish province of Tunceli, was the scene of mass murders between 1937-38 by the Turkish army in which between 20,000 and 30,000 Kurds died.

The massacres are commemorated on November 15 each year. On that day in 1937, the Kurdish leader Seyit Rıza and some of his followers, who had opposed the Turkish government, were hanged.

In a two-part series, a number of experts provide insights into key questions about the massacres, as more information and evidence has come to light in recent years.

“Fifteen years ago, we couldn’t say many things with certainty, now we can. It was not only about the destruction of one’s own Dersim culture, but also about the destruction of human lives. It was the intention to kill many Kurds. It is also striking that some Turkish dignitaries who played a key role in the mass killings in Dersim were involved in the Armenian Genocide in 1915,” he said.

A Turkish historian recently discovered the diary of a Turkish soldier who took part in the 1937-38 genocide in the Kurdish-majority province of Dersim, eastern Turkey.

Dersim Jenosidi devletin inkara gücünün yetmediği kadar açık olan bir icraatıdır. Bunun en bariz kanıtı bir bölgeye özgü çıkardıkları ve “Tunceli Kanunu” diye tanımladıkları belgelerdir. Zira buraya özgü çıkarılan kanun diğer katliamların “Jenosid olmadığı” anlamına gelmez.

In 1990 was published there a book in Turkey with a title, that the only party then in Turkey accused of genocide. According to the book, the party a genocide had exported in the Kurdish district of Dersim. The book became at the same time bans and it saw to not for the debate on which the writer and sociologist, Ismail hoped had. Was the first and for a long time the only that in all openness the Turkish official ideology and administration opposite the Kurds criticized. [1] He began in 1969 with its study of the social economic conditions of Turkish Koerdistan with a whole series of increasing polemic writings. He has a large price paid for its moral and intellectual courage; all its books its bans and he remained more than ten year in the prison for its books. The mass slaughters of the book of treated the pacificatie of the rebel scholar Kurdish district of Dersim (these becomes now Tunceli named) in 1937 and 1938. The events its one of the most black pages in history of the republic Turkey. On the book of the crtical sociologist was not reacted or been wrong reproduce to by most historians, as well foreign historians as Turkish. While the campaign against Dersim further went, saw to the Turkish authorities for it that little information to disposition came for the outside world. The diplomatic observanten in Ankara were of it conscious that it large military operations were, but she knew actual not what it precise at the hand was.

On that day, Kurds commemorate the victims of the massacre attempted against the Kurdish province of Dersim in 1937 and 1938. The Turkish armed forces bombed houses, forests and caves, using even poison gas, to kill people indiscriminately in an attempt to exterminate an entire community and its culture.