Mehdî Mêhvane 2 – Xeleka 8 | مەهدی مێهڤانە ٢ – خەلەکا ٨

#Dersim #Dersimê #Kurdistan #Xarpet #Elih #batman #kurtalan #Misircê #Kürdilan #Kurdilan #Ağrı #HDP #DBP #iyiparti #CemilTaşkesen #Rojava #tezkere #hayır #bitlis

Summary, in English

Environmental destruction has long been used as a military strategy in times of conflict. A long-term example of environmental destruction in a conflict zone can be found in Dersim/Tunceli province, located in Eastern Turkey. In the last century, at least two military operations negatively impacted Dersim’s population and environment: 1937–38 and 1993–94. Both conflict and environmental destruction in the region continued after the 1990s. Particularly after July 2015, when the brief peace process that began in 2013 ended, conflict between the Turkish state and the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) resumed and questions arose about the cause of forest fires in Dersim. In this research we investigate whether there is a relationship between conflict and forest fires in Dersim. This is denied by the Turkish state but asserted by many Dersim residents, civil society groups, and political parties. We use a multi-disciplinary approach, combining methods of qualitative analysis of print media (newspapers), social media (Twitter), and local accounts, together with quantitative methods: remote sensing and spatial analysis. Interdisciplinary analysis combining quantitative datasets with in-depth, qualitative data allows a better understanding of the role of conflict in potentially exacerbating the frequency and severity of forest fires. Although we cannot determine the cause of the fires, the results of our statistical analysis suggest a significant relationship between fires and conflict in Dersim, indicating that the incidence of conflicts is generally correlated with the number of fires.

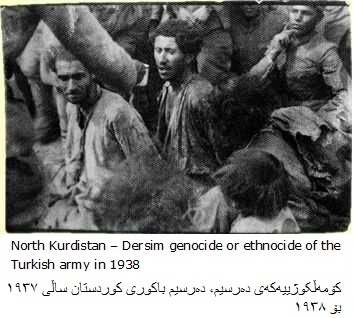

The Dersim region, overwhelmingly populated by Alevi Kurds, resisted the centralization policies of the Ottoman Empire for many decades. While the Alevi Kurds wanted to continue their indigenous cultural and political autonomy, this was considered a threat to the sovereignty of the newly established Turkish Republic (1923). Seyit Riza was one of the most prominent figures in the region, not only as the leader of the Hesenan tribe; he was also seen as a religious figure by the Alevi Kurds in Dersim. In 1937-38, the Turkish military started two major military operations targeting the Dersim region, with the aim of breaking the armed resistance organized by local militias. Gross human rights violations took place in Dersim during these military operations. Although the exact number is still unknown, Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan has said that state documents indicate 13,806 people were killed in the campaign. In January 1937, Seyit Riza sent his son to Aptullah Alpdogan (the commander of a military division in the region governed by emergency law) to find a way to end the armed clashes and mass killings. But Riza’s son was killed, and clashes continued relentlessly. At the end of the year, after Alpdogan promised to spare his life, Riza turned himself in to prevent further killings. We know what happened to Riza through the testimony of Ihsan Sabri, a state official who witnessed his execution (Çaglayangil later became Minister of Foreign Affairs). A quick trial was held, and the verdict read to Riza; he could not understand it, as he was unable to speak Turkish. Riza was sentenced to death and executed immediately.

Military operations did not stop or lose momentum and gross human rights violations continued, including aerial bombardment. Ultimately, the remaining Alevi Kurds were forced to migrate to the western regions of Turkey. Since the archives of the Turkish military are not yet accessible, it is not known what happened to Seyit Riza’s body or where he was buried. Therefore, Seyit Riza’s grandchildren have demanded to be told where his body was taken or buried. Discussions about the Dersim massacre intensified in the mainstream media after a speech by Onur Oymen, a deputy for the Republican People’s Party, in the National Assembly in 2009 in which he called the state policy of killings in Dersim “legitimate.” Since then, Riza’s grandchildren have become more vocal in their demands. But there has been no legal resolution to the questions surrounding his death as yet, and military officials have remained silent.

Hewlêr (Rûdaw) – Li bajarê Dêrsimê yê Bakurê Kurdistanê ku weke yek ji bajarên herî bedew ên Kurdistanê tê zanîn, bi kêmbûna ava bendavan û golan re, şûnûwarên dîrokî derketine ser erdê.

Li Geliyê Gemîciyê ya ser bi bajarokê Çemişgezeka Dêrsimê ya Bakurê Kurdistanê bi hatina biharê dîmenên bêhempa yên şûnwarên dîrokî, kultûrî û sirûştî derketin holê.

Di salên derbasbûyî de jî bi sed hezaran geştyaran berê xwe dan bajarê Dêrsimê û li nava xwezaya wî bajarî de digeriyan. Îsal jî ji ber qedexeyan û kêmbûna çûn û hatinê, piraniya navçeyên wê parêzgehê şîn bûne û dîmenên gelek balkêş derketine holê. Dêrsim ji bilî xweşikiya xwezayî, ji bo çendîn ajelan jî weke navçeyekî guncaw û aram e.

Bi kêmbûna ava gola bendava Kebanê li Gelî, Kenîseya Dirokî ya Miyadîn û şunwarên kevin ên di bin avê de mabûn, hatine xuyakirin. Dema dîmen bi hevre dibin yek, bi taybetî dema ku roj diçe ava, dîmenên çiya û teyisandina daristanê li ser avê ciwanî balê dikşîne.

Wênegir Malik Kaya dibêje: “Em dixwazin ciwaniya sirûştiya welatê xwe bo cîhanê bidin nasîn. Ne tenê Kinîseya Miyadînê, lê gelek cihên din jî hene ku gelekî hêjane û divê bên nûjenkirin. Em dixwazin ev cihên ciwan bo geştiyariyê bêne vekirin. Me gelek dîmenên ciwan û hêja girtine. Dema me ji bilindahiyê dîmenên gelî girtin, dîmen ne kêmî yên derya Ege û derya Spî ne.”

Geliyê Gemîcî di navbera çiyayê Kirklara ku li derdora gundê Alçilî ye,bi zêdebûna şînkayî û jiyana xwezayî balê dikşîne.

Welatî Fatih Karatepe jî got: “Ji ber ku ev der şûnwarekî kevn e her cor dar lê hene. Ez gelek caran derdikevim ser bilindahiya gelî, û li xweza û şînahiya Gola Bendava Kebanê temaşe dikim. Ez bi wî awayî aram dibim. Ev der ji ber Gola Bendava Kebanê hatiye ji bîrkirin. Lê ji ber niha av kêm bûye kinîse û cihên kevin têne xuyakirin. Kesên ku dikevin nav kinîsê qubbe, sitûnên dîrokî û çawahiya avakirina wan jî dibînin.”

Ligel ajelên ku neslê wan tên parastin wek werşek, hirçê gewr û pezkovî, û bi sedan corên çûkan jî li vir dijîn. Xwezaya ku bi darên behîv, tû, mazî û guhijan xemilî ye, wiha dike ev der zêdetir bala xelkê bikişîne. Ji ber vê yekî jî di her demê de ji bajar û bajarokên derdorê gelek kes ji bo temaşekirin û dîmengirtinê diçin wê derê.

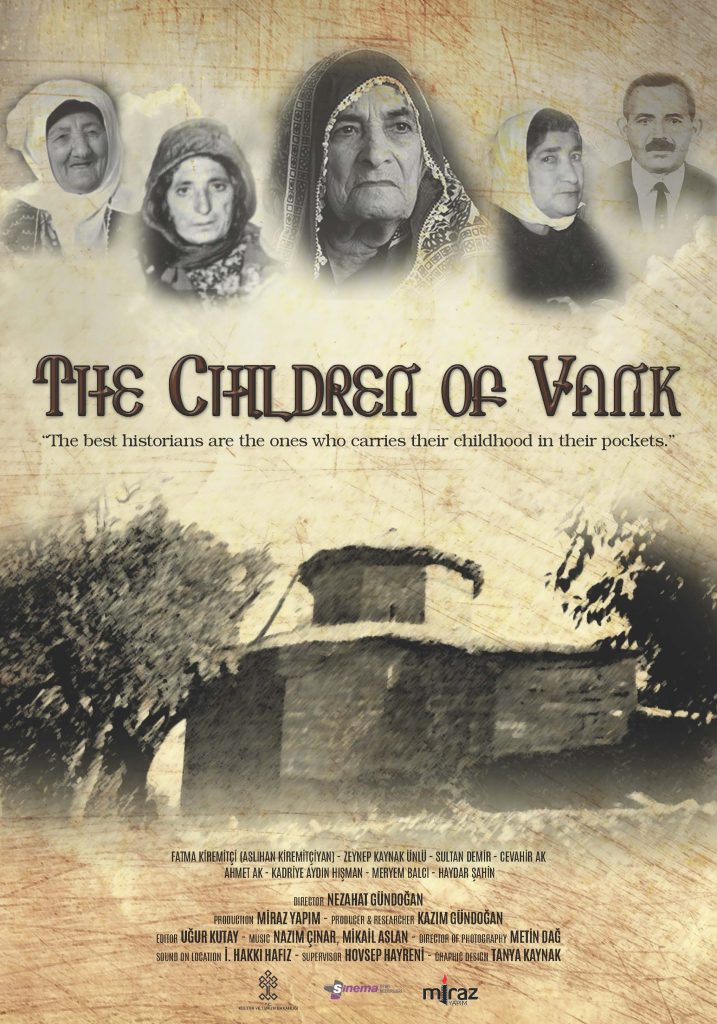

NEW YORK (A.W.)—In recent years, there has been a growing awareness of, and interest in, exhuming the stories of Islamized Armenians in Turkey. Though filmmaker Nezahat Gündoğan did not initially seek to portray the account of this “hidden” community, after researching the project for four years, she determined that it absolutely had to be told. Her documentary, The Children of Vank (“Vank’in Çocuklari”), weaves together the stories of an Islamized Armenian family who survived both the 1915 Armenian Genocide and the Dersim Massacre of 1938, unraveling the truth behind their lost Armenian identity.

A Turkish historian recently discovered the diary of a Turkish soldier who took part in the 1937-38 genocide in the Kurdish-majority province of Dersim, eastern Turkey.

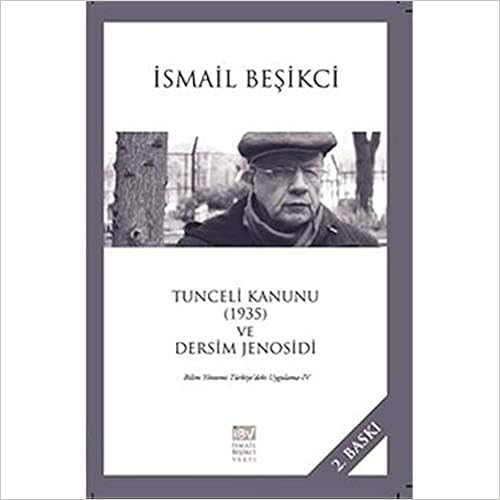

Dersim Jenosidi devletin inkara gücünün yetmediği kadar açık olan bir icraatıdır. Bunun en bariz kanıtı bir bölgeye özgü çıkardıkları ve “Tunceli Kanunu” diye tanımladıkları belgelerdir. Zira buraya özgü çıkarılan kanun diğer katliamların “Jenosid olmadığı” anlamına gelmez.

In 1990 was published there a book in Turkey with a title, that the only party then in Turkey accused of genocide. According to the book, the party a genocide had exported in the Kurdish district of Dersim. The book became at the same time bans and it saw to not for the debate on which the writer and sociologist, Ismail hoped had. Was the first and for a long time the only that in all openness the Turkish official ideology and administration opposite the Kurds criticized. [1] He began in 1969 with its study of the social economic conditions of Turkish Koerdistan with a whole series of increasing polemic writings. He has a large price paid for its moral and intellectual courage; all its books its bans and he remained more than ten year in the prison for its books. The mass slaughters of the book of treated the pacificatie of the rebel scholar Kurdish district of Dersim (these becomes now Tunceli named) in 1937 and 1938. The events its one of the most black pages in history of the republic Turkey. On the book of the crtical sociologist was not reacted or been wrong reproduce to by most historians, as well foreign historians as Turkish. While the campaign against Dersim further went, saw to the Turkish authorities for it that little information to disposition came for the outside world. The diplomatic observanten in Ankara were of it conscious that it large military operations were, but she knew actual not what it precise at the hand was.

On that day, Kurds commemorate the victims of the massacre attempted against the Kurdish province of Dersim in 1937 and 1938. The Turkish armed forces bombed houses, forests and caves, using even poison gas, to kill people indiscriminately in an attempt to exterminate an entire community and its culture.

On January 6, 2008, newspapers in the province of Tunceli in eastern Turkey appeared festooned with the holiday wishes, “May your Gaghand be merry.” [1] Celebrated on the same day as Armenian Christmas and bearing the same name, Gaghand is an important, if almost forgotten event in the religious calendar of Tunceli, or Dersim, to use the area’s historical appellation. In the villages of Dersim, bearded men calling themselves Gaghand Baba (Father Christmas) pay visits to children and the elderly, offering them presents of sweets and pistachios. Historical accounts from the early twentieth century also mention a ritual administered by religious leaders the very same day and highly reminiscent of Holy Communion. [2]

The people of Dersim are not Christians, but Alevis, a catch-all term for a variety of ethno-religious minorities in Turkey whose core religious heritage is Islamic but whose beliefs and practices are highly varied and syncretistic. [3] In Dersim, Christian and other influences infuse a heterodox Islam of distant Shi‘i origin whose adherents do not normally pray in mosques, fast in Ramadan, accept the Qur’an as a source of jurisprudence or make the pilgrimage to Mecca. Like many Alevis, they do commemorate the martyrdom of Imam Hussein on the plains of Karbala’ in the month of Muharram, a reminder of the Shi‘i component of their tradition.